The man who would become the Exalted Cyclops of the local Ku Klux Klan probably wouldn't be who most people would expect. Political parties, ideologies, and terminology like "progressive" all meant something very different back then. Like today, there were different factions and disagreements complicating that too. From the 1918 "History of Champaign County" on John J. Reynolds:

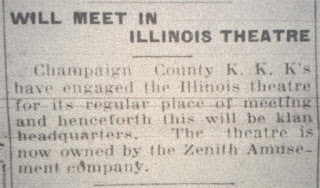

Pictures of the J.J. Reynolds grocery store are available in the Urbana Free Library's digital collection here, including this one showing a younger Jay (his familiar name) Reynolds in 1907:J.J. Reynolds owned the Zenith Amusement Company that would purchase the Illinois Theater in 1923 and make it the Klan's official headquarters. From the 11/8/1923 Mahomet Sucker State newspaper:

The theater and the Reynolds family itself publicly celebrated and dedicated both the new headquarters and a wedding of his daughter Helen Reynolds with a two day event including the then national leader of the Ku Klux Klan, Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans. From the 11/15, 11/20, 11/24/1923 Urbana Daily Courier:

From the bride's wedding book, as discovered by David Early in his research on the local Klan: "The ceremony was performed in the new home of Zenith Klan No. 56 Realm of Illinois KKK. The Klavern was arranged with three monster K's in rear, a large cross on either side, lighted, and the altar duly prepared in center and a semi-circle of Klansman and Klanswomen in full regalia as a background for the wedding. The contracting parties, in full regalia, stood in front of the altar, facing the east. The curtain raised at 8:25 and Rev. McMahon offered a beautiful opening prayer, then joined the ranks of Klansmen two paces to rear of Groom; O.K. Doney then bound Helen (Reynolds) and Harry (Lee) together by a beautiful Klan ceremony prayer. Prayer: McMahon. Bride & Groom introduced to Klansmen & Klanswomen, & received sign of greeting; introduced to throng of 1500 - hearty cheer of greeting...."

The marriage would last nearly five years, until Hellen Lee died of pneumonia in late 1928. Harry Lee would go on to remarry with the child of his first marriage residing with her grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. J.J. Reynolds. From the Courier 10/26/1928 and 1/7/1930:

By this time, however, the Illinois Theater had burned down. From the 4/4/1927 News-Gazette: