|

| Klanswomen at the 1925 Klan Parade on Washington. D.C. (From Smithsonian Magazine) |

The first local Klan stories I came across in 1925 would seem very typical of the previous years. There was a Klan visit and flag donation to the Emmanuel Mission church. Later there was also a visit to the Webber street church of Christ by Klansmen in full regalia, but now with Klanswomen in regalia as well. Typical Klan gifts of a flag and money were given and accepted. From the 1/5 and 1/20/1925 Champaign News-Gazette:

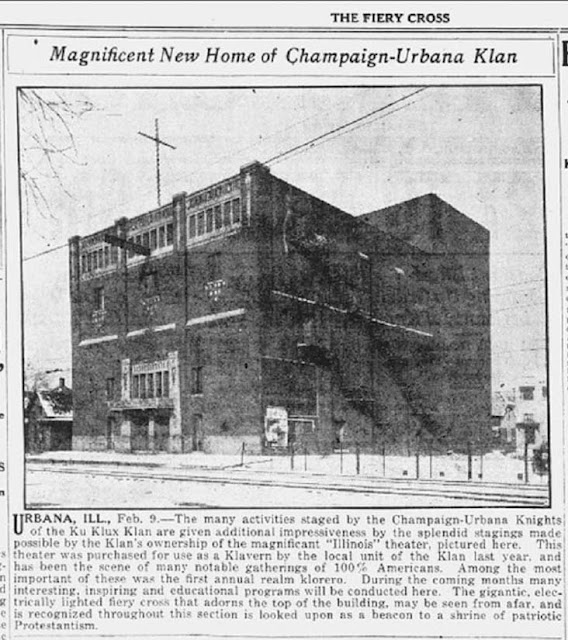

An earlier announcement in the Urbana Daily Courier would mention a national lecturer coming to the local Klan headquarters at the Illinois Theater.

There were also continuing news articles about "unauthorized" cross burnings, an issue that the area that the local Klan leadership had been trying to tamp down on since prior to the November 1924 election. From the 1/15 and 1/19/1925 News-Gazette:

I can't yet confirm if Klan members were involved in the burnings of these crosses, but it is possible. The Klan almost always officially denied illegal activity, regardless of whether or not the Klan was involved. In the first case, however, there were multiple Frank Johnsons living in the area at this time, and one was certainly a dues paying Klan member (Klan number 1517) according to surviving financial records. Further research may be able to rule out or possibly confirm if they were one and the same.

The other case was murkier, because the apparent target of the cross burning, Bergan F. Morgan, was certainly a Klan member and also ran the local newspaper in Homer, Illinois. Ray Cunningham of the Homer Historical Society described him to me as one of the key Klan members in Homer, IL:

There were three key members of the Klan in Homer: Homer Enterprise editor Bergan Morgan (member no. 715), funeral home director Chester Morehouse (no. 1821), and grain merchant James Current (no. 1429). Morgan’s membership was not known at the time, but because the Enterprise was printing editorials favorable to the moral aims of the Klan, it was obvious to all where his sympathies lay. Chet Morehouse was a more active member of the Klan, and it is probable that he was a leader of the group in Homer. James Current’s activity in the Klan was allied with his strong moral stands. Current was a frequent guest minister at the Lost Grove and other area churches and an active member of the Methodist Church.

There will be a future post with more on area newspapers, Klan membership, support, and opposition. More Klan Homer, IL related news clippings are available here on our site. I haven't found any information that would suggest whether Morgan was targeted by someone meaning to out him a Klan member or possibly some sort of Klan infighting.

Infighting certainly wouldn't be out of the question, in spite of the local "Exalted Cyclops" J. J. Reynolds' denials. As we saw in a previous post, the national Klan leadership fight had already resulted in a very public murder in 1923, just prior to the Imperial Wizard's visit to Champaign-Urbana. There was a fight for leadership around the November 1924 elections as well. From the 11/9 and 11/10/1924 Chicago Tribune:

As the article notes, financial scandal and power struggles plagued the Illinois Klan leadership in 1924, much as it had the national leadership in 1923. It's very likely the local "Exalted Cyclops" or other local Klan representative attended the event along with others mentioned from downstate Illinois. Among the attendees was also the Urbana Klan's drum corps. From the 11/4/1924 Courier:

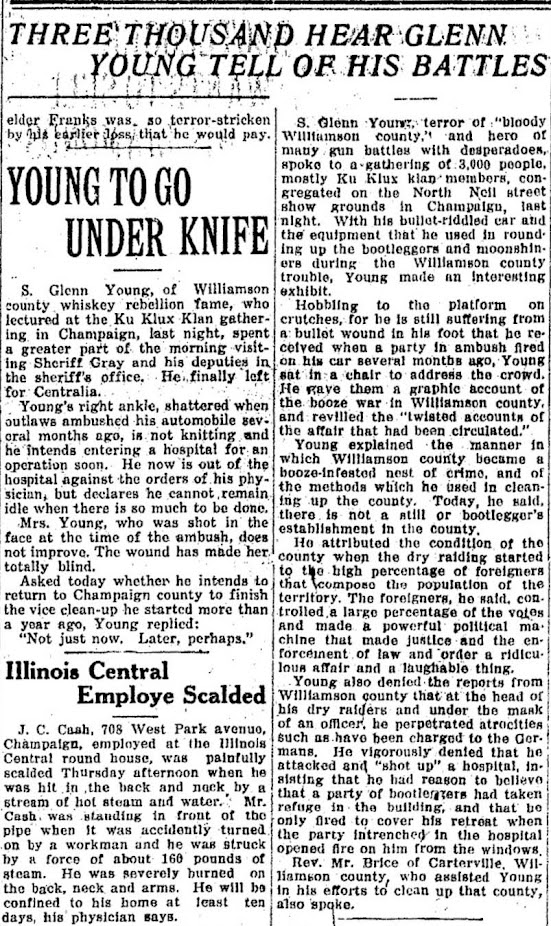

Also mentioned at that event was Klan raider S. Glenn Young, who had worked with local law enforcement prior to his rise to infamy in "Bloody Williamson" County. Young would finally die in a gunfight in Herrin, IL, in late January 1925. He died in the same town he briefly ruled over with his Klan army and their handmade star badges cut from tin. The Champaign County Sheriff John Gray and Urbana Chief of Police Roy Innes would attend his massive Klan funeral. Coverage of Young's death, funeral, and high praise from his longtime friend Sheriff Gray, from the 1/26 and 1/27/1925 Courier:

1925 saw Klan activity throughout the Champaign County area reported in local papers. In February, large events were reported in Homer, Monticello with participants from White Heath, and Ogden,

In March the local Klan packed the First Baptist church of Champaign and participated in the services. A flag donation was also given and accepted. From the 3/5/1925 News-Gazette:Also in March, the popular Indianapolis based Klan newspaper "The Fiery Cross" would highlight the local Klan headquarters and praise the large electric "fiery cross" on its roof next to downtown Urbana. From the 3/2/1925 Fiery Cross:

A local Klan meeting in Champaign was noted in the Courier on 4/27/1925 while highlighting local Gifford news and attendees from there:

A bit further South of us, a regional Klan minister and recruiter, J. F. McMahan, who operated heavily in Champaign County and the Twin Cities, lost an election for school board. He made more of an impact, however, as a campaign manager for the Klan backed mayoral candidate in Mattoon. Headline from the 4/22/1925 Mattoon Journal-Gazette:

The local Klan, Women's Klan auxiliary, and Junior Ku Klux Klan would participate in a massive Klan event there with Reverend McMahan's Christian church along with the Mattoon Klan. The overflowing crowds had to relocate to Peterson Park and there was a large public Klan procession with Klan decorated automobiles to the evening's events. From the 4/27/1925 Journal-Gazette:

Klan activity appeared to continue through the Summer of 1925, but coverage of area events that I found were mostly outside of the Twin Cities and in surrounding areas. The local headlines generally involved the Indiana Klan and its Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson. He had been charged with numerous crimes involving a young woman he had met at the Klan backed Indiana governor's inauguration festivities. The heinous details are available at this well-sourced article on the the Smithsonian Magazine website. Excerpt:

She died on April 14, nearly a month later, with her parents and nurse by her bedside. The official cause was mercury poisoning. Marion County prosecutor William Remy—one of the few officials Stephenson could not control—had him charged with rape, kidnapping, conspiracy and second-degree murder. His former political cronies, including Governor Jackson, swiftly abandoned him, and the Indiana Kourier called him an “enemy of the order.” Stephenson’s lawyers argued that Klan forces loyal to a political rival had set him up and questioned whether he could be held responsible for what was ultimately a suicide. “If this so-called dying declaration declares anything, it is a dying declaration of suicide, not homicide,” defense attorney Ephraim Inman said. “… Has everybody lost his head? Pray, are we all insane?”

Embarrassing headlines and horrific details about the scandal locally may have played a role in a lower public profile here. From the 4/3/1925 Courier prior to the victim's ultimate demise:

In August, local Klan minister and frequent spokesman, O. K. Doney held a Klan funeral for his Civil War Veteran father, Lysander Doney. Lysander Doney volunteered, re-enlisted and fought for the Union. The obituary suggests he shared his son's love of the second Klan movement, however, noting he was, "a member of the Church of Christ, the Odd Fellows and at heart a Klansman." From the 8/7/1925 Courier:

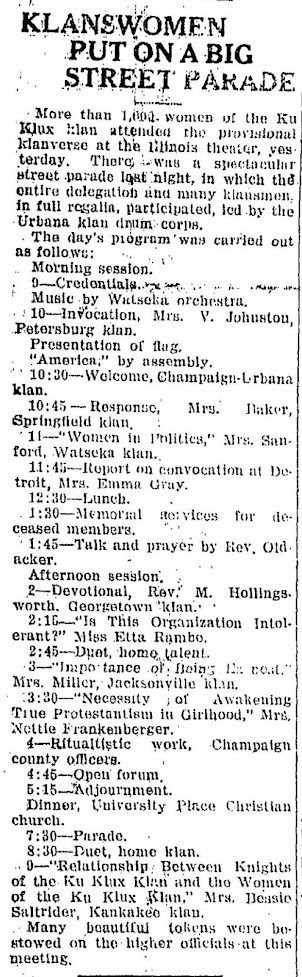

That same month the local Klan women's auxiliary put on a massive public parade along with local klansmen and their drum corps. It was part of a full day of events at the local Klan headquarters at the Illinois Theater. The 8/10 and 8/11/1925 Courier had an overview and the schedule of events, while the 8/11/1925 News-Gazette noted the state and national officers present for the convention:

October saw another supposedly "unauthorized" cross burning at the home of a Klan critic as well as local Klan members participating in large events in Springfield, IL. From the 10/7 Courier and 10/9/1925 News-Gazette:

November saw more Klan related stories and headlines from Indiana than local news. Locally there were typical stories of cross burnings and parades. For example there was an Armistice Day cross burning north of town in Rantoul. There were also initiations in the local Klan and women's auxiliary as well as a Klan parade through the business section of Champaign. From the 11/14 Courier and the 11/29/1925 News-Gazette:

But the attention on the Klan would be focused almost entirely in Indiana as its former Grand Dragon D. C. Stephenson was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Headline from the Indianapolis Times (click to enlarge):

The Courier would note his arrival to prison in its 11/21/1925 edition:

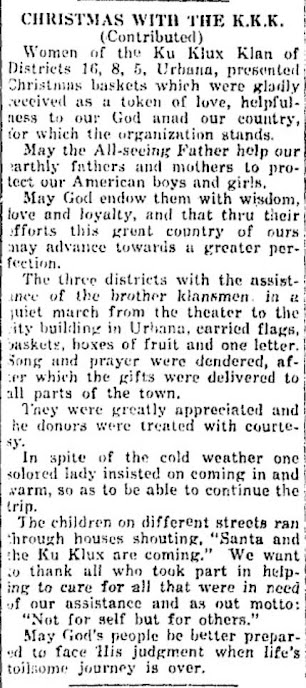

December would see the third annual Klan Christmas event for local children. The 1925 Christmas event included music by the "boys and girls glee clubs of the Urbana high school, under the leadership of Ray Dvorak," in addition to the Klan's own musical band. Dvorak is probably best known locally as the creator of the Chief Illiniwek halftime show at the University of Illinois along with Lester Leutwiler. He would do this in his role as assistant director of bands for the University the next year in 1926. The Chief Illiniwek tradition would carry on from 1926 to 2007. Dvorak would also help create the Three-In-One musical tradition that continues on without the Chief Illiniwek show. From the 12/21/1925 News-Gazette and Courier:

North of town in Rantoul, the Klan would also visit the Huling orphanage with gifts and holiday meals. The Courier coverage on 12/24/1925 added that a "a very interesting talk to the children was given" as well:

In the next C-U Klan post we'll continue to see the impact of the corruption and violence in the decline of the Klan locally and nationwide. The events and parades would become more sparse and the headquarters would literally burn to the ground. The Klan and its members, however, would continue on... often in positions of power.