Several area ministers helped propagandize and recruit for the Klan. Probably the most notorious in East Central Illinois was Reverend Jesse Forrest McMahan of Mattoon. He was usually listed in the papers as Reverend J. F. McMahan, although sometimes the reporters goofed the first name. He helped spread the Klan over a vast area of the State and not just Champaign County. Additional information on McMahan, including an attempted run for school board in 1925 is available in "Tale's of Cole's County" by Michael Kleen. There's also another post on McMahan's local political moves here. From the Mattoon Journal-Gazette on 11/25/1922:

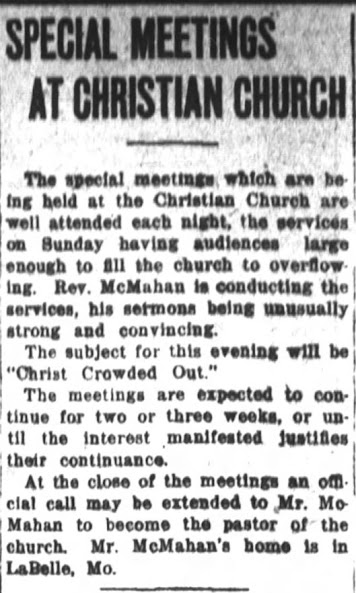

Reverend McMahan had come to Mattoon as part of special revival services around the beginning of 1920 and was asked to come on as the pastor of the local Christian church. From a Journal-Gazette clipping on 1/19/1920:

As noted in previous posts and pages, the Klan made its first public appearance in the usual way, in full regalia and with a gift to the local Protestant church. From the Journal-Gazette on 7/29/1922:

By October he was admitting openly what local folks had long suspected, that he was an open and unapologetic member of the Klan in his lecture tour around the State of Illinois. From the 10/17/1922 Journal-Gazette:

The Mattoon Klan itself was letting other area towns know about their presence and recruiting in the process around this same time. From the 10/31/1922 Journal-Gazette:

By December, internal power struggles with the Church were being resolved with aid of Klan visits and support for his side against the head of the Sunday School classes and trustees (click to enlarge these clippings from the 12/5/1922 Journal-Gazette):

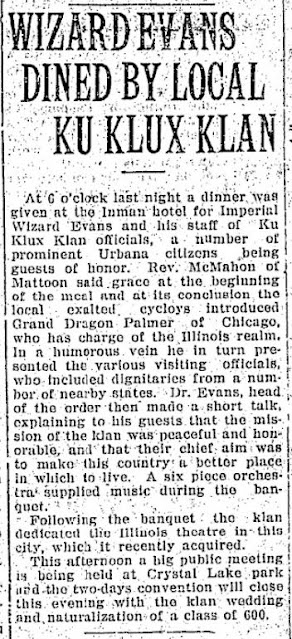

He was also present at the massive two day Klan convention in Champaign-Urbana attended by the national Imperial Wizard at the time, Hiram Evans, Illinois Grand Dragon Palmer, and our local Exalted Cyclops J. J. Reynolds. From the 11/24/1923 Courier:

And others, like this massive Klan gathering at Crystal Lake Park covered in the 8/24 and 9/25/1923 Courier:

But he was also a large part of spreading the Klan message and recruiting in the smaller communities in the area such as:

Atwood (2/28/1923 Courier):

Sidney (7/11/1923 Courier):

Pesotum (8/1/1923 Courier):

Villa Grove (8/11/1923 Courier):

Philo (8/14/1923 Courier):

Rantoul (10/3/1923 Courier):

Throughout this time his family was helping sell the Klan newspaper, "The Fiery Cross" and he was traveling to Indiana for Klan events and other meetings. Indiana was the central hub of the second Ku Klux Klan movement in the North. From the 5/19 and 6/27/1923 Courier:

By early 1924 he was openly announcing Klan related sermons in the local Mattoon paper at the First Christian Church of Mattoon. From the 3/14 and 3/28/1924 Journal-Gazette:

He also continued his efforts to spread the Klan message and recruit within Champaign County:

The ill-fated Homer Klan event interrupted by drownings:

Mahomet (8/1/1924 News-Gazette and 8/7/1924 Mahomet Sucker State):

Urbana, where he was even in the Klan advertisement as well (8/29/1924 Courier):

Tolono (9/17/1924 Courier):

The last reported Klan function I found coverage of with Reverend McMahan was for a Klan funeral in the 5/11/1927 Journal-Gazette:

He and his family were still engaged in the community, but he stopped talking about the Klan, at least in public. Local coverage of his family's comings and goings didn't appear to inquire into his Klan activities and everyone just seemed to move on. In 1956, for example, the paper had a puff piece about his wife's costume shop that mentioned him. It notes he had been a priest at the local Christian church and that he and his wife also ran an apartment house.

The irony of this notorious Klan family selling costumes and masks for dress up in the area didn't get a mention. From the 10/30/1956 Journal-Gazette (click to enlarge):

Reverend McMahan died shortly afterward in 1957. His obituary from the 4/10/1957 Journal-Gazette does not mention his years of open Klan activity or hint of anything controversial in his past:

The small town Mattoon Journal-Gazette was almost certainly aware of his history, but like everyone else, people just didn't talk about it. The Journal-Gazette wouldn't mention it, as far as I could find, until 1972 as part of a few "this day in history" style blurbs called "Glancing Back" under "50 years ago today (1922)" on 7/29, 8/12, and 8/14/1972:

This follows a trend of Klan leaders and members, organizers, ministers, and so on who just moved on with their lives. They never had to atone or apologize for their actions or beliefs. They weren't ostracized or even asked about something that clearly they wanted to keep quiet and in the past. Unfortunately, this trend will bear out in upcoming posts about other Klan leaders and open Klan ministers in future posts.

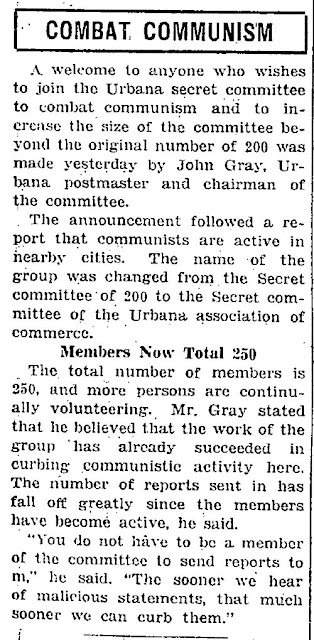

There was no conspiracy. Just a culture that had long encouraged letting the past be the past since the death of Reconstruction and into the racial Nadir of American history. Records didn't have to be destroyed or altered. It required no effort at all. Later we'll see that when people attempted to raise the issue they were vilified as unamerican, communist fifth columns, and other dangerous radicals. Whether it was during the Cold War or the War on Terror.

No comments:

Post a Comment