As far as local Klan ministers go, Oliver Kinsey Doney probably made the most headlines as an outspoken proponent and member of the Champaign County Ku Klux Klan. He began as a pretty typical local attorney. He was featured in the 1905 edition of the History of Champaign County (volume 2):

OLIVER KINSEY DONEY, a minister and lawyer, of Urbana, Ill., was born in Deerfield, Mo., November 30, 1873, the son of Lysander and Cynthia A. (Hill) Doney. The former was a veteran of the Civil War whose first enlistment for a period of three months so inspired him with zeal, that at the expiration of this term, he immediately reenlisted for the entire war. At the Battle of Chickamauga he was twice wounded, and although he bravely kept on, he was at length compelled to fall out of line at Atlanta, in the famous "March to the Sea." The mother was, in her youth, a somewhat gifted singer, and to her san she transmitted not alone her contour of features, but a natural musical ability...

The children had no opportunity to attend school until 1885, when the family removed to Tolono, Ill., but here the two started in the same grade graduating together from the high school in 1893. Then came a separation hard to bear, since the brother and sister were like twins, for in the fall of that year the lad entered the University of Illinois, the sister's ill-health detaining her at home. Mr. Doney spent two years at this institution of learning, taught school for a term, and then decided to study law.

In March, 1899, he was admitted to the bar. He then reentered the university and graduated with the class of 1900, receiving the degree of LL. B. Since then he has practiced law, specializing as an abstractor. He is an earnest advocate of the cause of prohibition, declaring that every voter at every election should cast his vote to destroy the liquor traffic. His ambition had been, since his boyhood, to become a minister not a mere preacher, but a minister. With this end in view he made a special study of the gospels, and was ordained April 5, 1903, not as a minister of any special denomination, but of the Church Universal the Church of Christ...On August 17, 1899, Mr. Doney was married to Hattie Myrtle, a daughter of Mr. and Mrs. John W. Shuck, of Urbana, Ill. Mr. Shuck is a veteran of the Civil War. Since May, 1903, Mr. Doney has been preaching with marked success at Homer, Ill.

As the Klan was emerging locally, O. K. Doney was retiring from the Christian church of Villa Grove. He was soon to be replaced by Reverend Hollingsworth, who would also become an outspoken advocate for the local Klan. From the 12/19/1922 Urbana Daily Courier and Villa Grove News:

Within months, O. K. Doney was openly participating in Klan events. An early example was an event honoring local WWI veteran Lt. Ennis G. Stillwell. From the 5/30/1923 Champaign News-Gazette:

One of the tactics by the second Klan in the 1920s was setting up a debate platform, often with a local Catholic leader, that helped amplify the Klan position regardless of the event itself. From the announcements in the 8/23/1923 Courier and the coverage in the Rantoul Weekly Press on 8/30/1923:

I don't have any information on Thomas Sunderland being anything other than a well-intentioned and good faith participant in these debates. It's quite possible he was hoping his engagement would help shine a light on the Klan's ideological flaws. Unfortunately, any such arguments did not appear in the local coverage that I could find.

O. K. Doney would also be involved in the massive naturalization, parade, and Klan meeting at Crystal Lake Park in September of that year. From the 9/25/1923 Courier coverage:

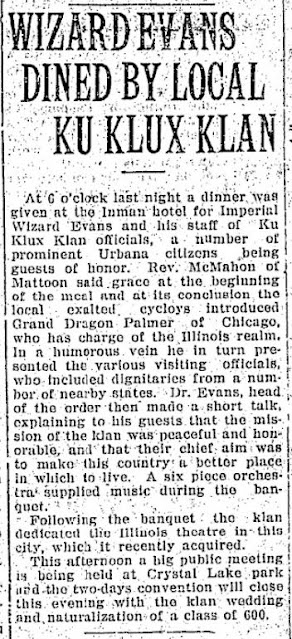

O. K. Doney would also mingle with the Imperial Wizard of the national Klan organization and the Grand Dragon of Illinois during the massive convention here in 1923. He performed the Klan wedding ceremony that completed that convention. From the 11/20 and 11/24/1923 Courier:

Other Klan ministers also participated in that convention, including J. F. McMahan covered in another post here. From the Courier coverage of the convention on 11/24/1923 and a 11/20/1923 advertisement for the events in the same paper:

As a well known figure for the local Klan, the Courier would sometimes treat him like a spokesman on local Klan matters. From the 1/7/1924 Courier:

The Klansman in this case was a local business man and grocery store owner, separated from his wife, who claimed he was in the inescapable "clutches" of a local white-passing Black prostitute. From the 12/28/1923 Courier:

As one can imagine, the marriage ended in divorce soon after.

In another unusual twist, O. K. Doney's Civil War veteran father received a Klan funeral, with full regalia and Klan drum corps. In the 8/7/1925 Courier coverage, his memberships are listed as "the Church of Christ, the Odd Fellows and at heart a Klansman." It's hard to know if he would have appreciated that description as a Union veteran or if his son inserted that on his behalf. The bizarre nature of 1920s politics make either a possibility.

The next local coverage I could find on O. K. Doney was with the passing of his wife, who had apparently been ill for some time. From the 1/13 and 1/14/1931 News-Gazette:

It's after this funeral that it appears that O. K. Doney may have soon moved to Chatham, IL according to his later obituaries (below). He pops up in local coverage, however, while working for the WPA (Works Progress Administration) under FDR's New Deal programs. In the 12/23/1935 Courier it's noted that he's working on collecting local information for the Illinois issue of the American Guide Series of the WPA.

A couple years later he's noted in the 10/13/1937 Courier organizing local government archives for the WPA:

No mention of his prominent Klan activities, support of the Klan, or even his membership were noted in his obituaries locally. Below are the mentions of his death in the 6/23/1941 Courier and News-Gazette as well as the 6/26/1941 Villa Grove News:

There may be an addendum to this post if I receive additional information on his final years in Chatham. From the information I have locally, it appears that like other Klan ministers, he went on to live a normal life. His public Klan background wasn't a hindrance or even an awkward mention in his obituary. It was just left in the past.