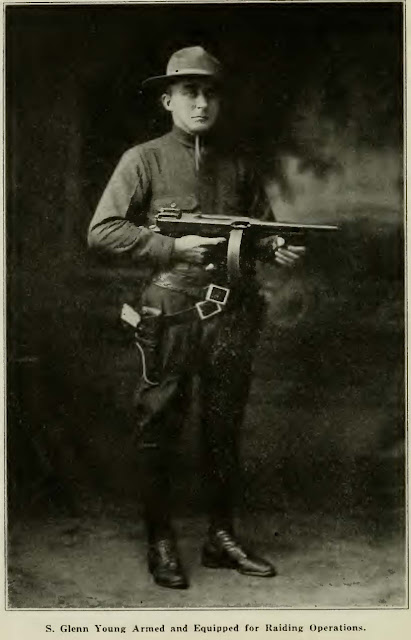

A more well known bit of Southern Illinois history is "Bloody Williamson" where Ku Klux Klan raiders went to war with with anti-Klan bootleggers and Knights of the Flaming Circle. Various law enforcement found themselves on either side of the battle lines. Klan Raider S. Glenn Young would eventually have the Sheriff and Mayor arrested and briefly become dictator of the little town of Herrin. An army of Klan members with handmade stars cut from tin cans would hold the town until National Guard units (some from the Champaign County) assumed authority. The story is incredible and even crazier than it sounds. At one point the Sheriff of Williamson, along with others, were held in the Champaign County jail for their own protection. From the 2/11/1924 News-Gazette:

This page doesn't get into the whole story of Williamson, which is bettered covered by the book linked above and other sources. That tale is complicated and it can be difficult to know who or if there are any "good guys" in the story. Before S. Glenn Young went to Williamson, he spent several months raiding bootleggers right here in Champaign County alongside local police. His extremely pro-Klan biography gives a shoutout to Urbana and the Champaign County Sheriff:

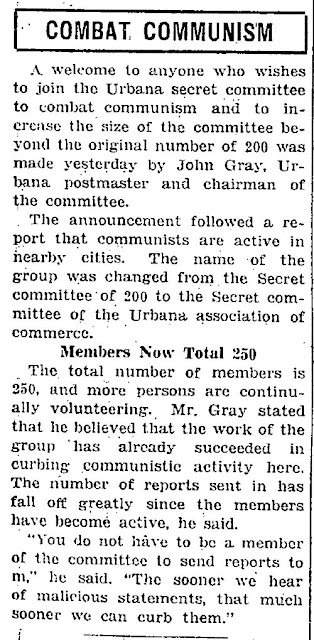

As a general rule, it's probably not a good sign when an extremely pro-Klan book has to assure the reader that you aren't a Klansman, just really splendid by Klan standards. Sheriff Gray would return the sentiment, however, becoming close friends with the notorious Klansman during their work together in Champaign County. He would go on to speak highly of his friend, criticizing the press coverage of him, and amplify concerns about foreigners and outsiders in defense of Young:

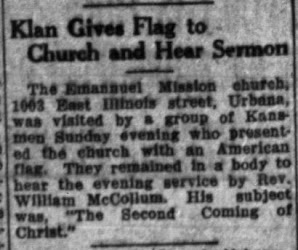

Glenn Young became a Klan leader in East St. Louis after his raiding days in Williamson County. He did speaking tours to Klan gatherings here and elsewhere. His speaking events later included the bullet riddled car he and his wife were ambushed in, leaving both with permanent injuries. In Champaign, the Klan rally he spoke at included this, but also compliments to the County Sheriff and Urbana police departments. He seemed to imply that the Champaign police department fell short in some way:

The bullet-riddled car he displayed had been a new vehicle purchased for him by the Williamson Klan in gratitude for his efforts.

This was in addition the salary the Klan had paid him for his services as a raider of bootleggers. The concept of "professional" policing was still in its infancy at this time in the early 1920s (The Mississippi Department of Education has a brief overview of the policing history timeline in the United States here). At it turned out, S. Glenn Young was no longer a prohibition agent, or an active federal agent of any kind anymore. Not just when he was freelancing for the Klan under that supposed authority. But even while he was raiding along side local law enforcement in Champaign County. From "Bloody Williamson:"

Young was exonerated by a coroner’s jury but indicted for murder by the Madison County grand jury. The Prohibition Unit suspended him on December 20, 1920, pending the result of its own investigation. On the ground that he was a federal officer at the time of the offense, the case was taken from Madison County and set for trial in the U.S. District Court at Springfield...

Young was a free man, but any elation he may have felt at his acquittal must have been dampened by the knowledge that he had no job. Two weeks earlier he had been dismissed as a prohibition agent, with the dismissal dated December 10, 1920, when he had been suspended.

His discharge was the result of an investigation, conducted by two special agents, that the Prohibition Unit initiated after he killed Vukovic. In that case the agents concluded that Young had acted in self-defense, but that he did not exercise the caution and discretion to be expected of a government officer when he entered the house without a search warrant. In other instances of alleged improper or unlawful conduct the agents found Young guilty. He had, as charged, presented a fictitious claim for auto hire; he had inspired the East St. Louis Journal articles, which were held to be “improper newspaper publicity”; he had continued to represent himself as a prohibition agent after his suspension.

There were reports that Young's publicity stunts and methods had upset Klan leadership and led to his ejection from the organization, but his biographer, who published the book together with his widow disputed those reports. He quoted the Grand Titan of Illinois as saying that Young remained in good standing with the organization:

There's a theme of animosity against the press by Sheriff Gray, Young's biographers, and the Klan more generally. In the biography it is summed up as the result of a "Romanized-Judaized press" viciously attacking them with lies. There may be some parallels to the "Lügenpresse" rhetoric that emerged in Germany, but direct connections are harder to discern than many shared influences and international conspiracies of the age.

The biography assures us that Klan raiders, and certainly not Glenn Young, had no prejudice against other religions or races. In addition to these denials of hate or prejudice, however, they noted the indisputable reality and necessity for white supremacy in a section called "Klan Principles are American and Christian." Excerpt:

Sheriff John Gray would go on to become a local Postmaster and later Mayor of Urbana. He would be invited to be and act as a pallbearer for the Exalted Cyclops of the local Ku Klux Klan in 1935:

At his funeral former Sheriff and Mayor John Gray would be praised and described as despising "the very appearance of evil."